1. (2010-now) The reception of classical concepts, myth and art in editorial cartoons.

Democracy and popular media: the reception of classical myths, ideas, imagery, events and statesmen in political cartoons from the turn of the 20th century to the present day

There is much debate, even outside of the “classics world”, on who reads classics, whether it is only of interest to the elites of this world, or whether it is useful to non-specialists. There is however a huge and uncharted territory which has been overlooked by most classicists: the world of editorial cartoons. They are very accessible, challenging and mass-produced, in numerous languages and throughout the world.

Indeed, what should we make of the many thousands of editorial cartoons in popular and prominent newspapers, propaganda leaflets, from the 19th century to this day, which make classical references, which use (and abuse) Greek and Roman visual myths, events or statesmen, to mock current affairs? Printed newspapers and online papers have grown exponentially in recent years, and their readership has increased not only in numbers but also in popularity, encompassing readers from all social horizons. Newspapers thrive in democracies.

This project, supported by a very large and growing database of political cartoons with classical references, includes mainly publications from most European countries, the USA and Canada, but also some random finds from more “exotic” countries (e.g. Singapore). The many cartoons mocking the ancient world are not considered in this project: only those using the ancient world to comment on current affairs.

There needs to be a move, stronger than ever to study “popular”; art forms, maybe part of what we call media today (theatre, films, documentaries, comics, art, visual and verbal humour, poetics, political rhetoric; new media such as the internet) to tap in the immense reservoir of references to the classical world and understand better both our own categories of thought, and our special relationship with Greek and Roman antiquity.

Research output: a series of articles (2010; In Press; In Preparation); 1 large monograph on the topic (In preparation); 5 conference papers; a growing database hosted on classicalreception.eu . The Cartoons DB currently (08/10/2022) holds 3287 cartoons (335 cartoonists, 49 countries, 147 different ancient themes, 20th-21st centuries, 127 newspapers).

2. (2010-now) The history of medicine, Roman terracotta and the function of pathological grotesques.

The meaning and function of ancient grotesque terracotta figurines has been debated since the time of Charcot and Regnault, who first “diagnosed” a pathological inspiration in the grotesquely deformed bodies of terracotta statuettes found by the thousands in various archaeological excavations of the Mediterranean and dating from the 3rd century B.C.E. to the 3rd century A.D. Yet the iconography of these grotesque terracotta figurines is extremely complex to pinpoint with any certitude.

There are three main spheres of interpretation: visual humour, theatrical imagery, and specific “portraits” of known pathologies. Their function may have been to amuse, to avert evil, as a memento of comic plays, or even for medical study. These grotesque figurines often lack an archaeological context to be fully understood, which is a little like diagnosing a patient over the telephone.

An interdisciplinary research project between the history of medicine and archaeology. With the collaboration of Prof. L. Lorusso, Clinical neurologist, in Chiari, Italy and Dr. Celso Zappalà, Obstetrician Gynaecologist, Torino, Italy.

Research output: 4 articles ; 4 conference papers.

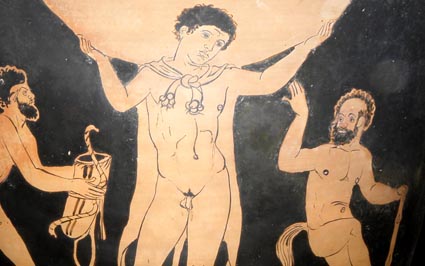

3. (1999-now) Visual humour in Ancient Greece.

This project which began in 1999 as a D.Phil focussed largely on comic images in ancient Greek vase-painting, a relatively neglected subject at the time. It involved analysing images on over 40.000 Greek vases stored in over 30 European museums, and carrying out a reconnaissance survey in and around the Kabirion Sanctuary, Thebes (Greece). I also carried out a systematic analysis of the entire Beazley archive and the Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum. I worked at the Beazley Archive during my D.Phil and for another year and a half as a full-time researcher for the CVA project. This research resulted in an extensive database, the foundation of my D.Phil, articles and a monograph. I drew many vases during that period, including over a hundred vectorised line-drawings of vase paintings.

The Research questions focused on identifying visual humour in ancient Greece (mainly Athens and Boeotia), from the 6th to the 4th centuries B.C., through unchanged mechanisms/genres (surprise, parody, caricature, situation comedy); and comparing each comic image to a series of ‘usual’ or ‘serious’ representations. The decorated Greek vases are found in the hundreds of thousands, and depict minute details of everyday life and mythology. They also mock many aspects of social and political life, as well as the religious and the mythological spheres; they offer a humorous perspective on popular subjects such as women, foreigners, workers, peasants, poliadic and Dionysian cult (in Attica but also in Boeotia: a chapter of Mitchell In Press 2009 concerns the Kabirion Sanctuary near Thebes) and democracy. The study enabled me to establish certain patterns within painters’ workshops, where certain painters seem to almost specialise in comic scenes. A principal contention was that the products were relatively cheap to produce and purchase, and that because they were made by artisans for the market rather than for a patron, they exhibited a freedom of expression which was lacking in most other patronised art forms of the 6th to the 4th centuries B.C. Just as Aristophanic comedies provide insights into general trends in Greek culture — to win democratically at the yearly dramatic competitions a playwright had to offer something to please most citizens — Greek vases were aimed at universal appeal, or in other words, at being purchased! Humour was a powerful marketing tool in ancient Athens just as it is today in modern advertising .On the one hand, I interpret the comic images on the ancient Greek vases as reflections of general public sentiments rather than those of the intellectual elite, and on the other, I argue that the artists who produced them enjoyed a freedom of expression which was a direct outcome of the new democratic rule.

Research output: Oxford D.Phil 2002, a series of articles (2000, 2004, 2007, 2014, 2016, 2021, 2022) a monograph (Cambridge University Press 2009, 2nd ed. 2012, 3rd ed. 2013), and a number of invited lectures.

![Vicky [Victor Weisz]: Evening Standard, 22.11.1960: click on the picture for a larger view Photograph © Alexandre G. Mitchell.](https://alexmitchell.net/images/1_m.jpg)