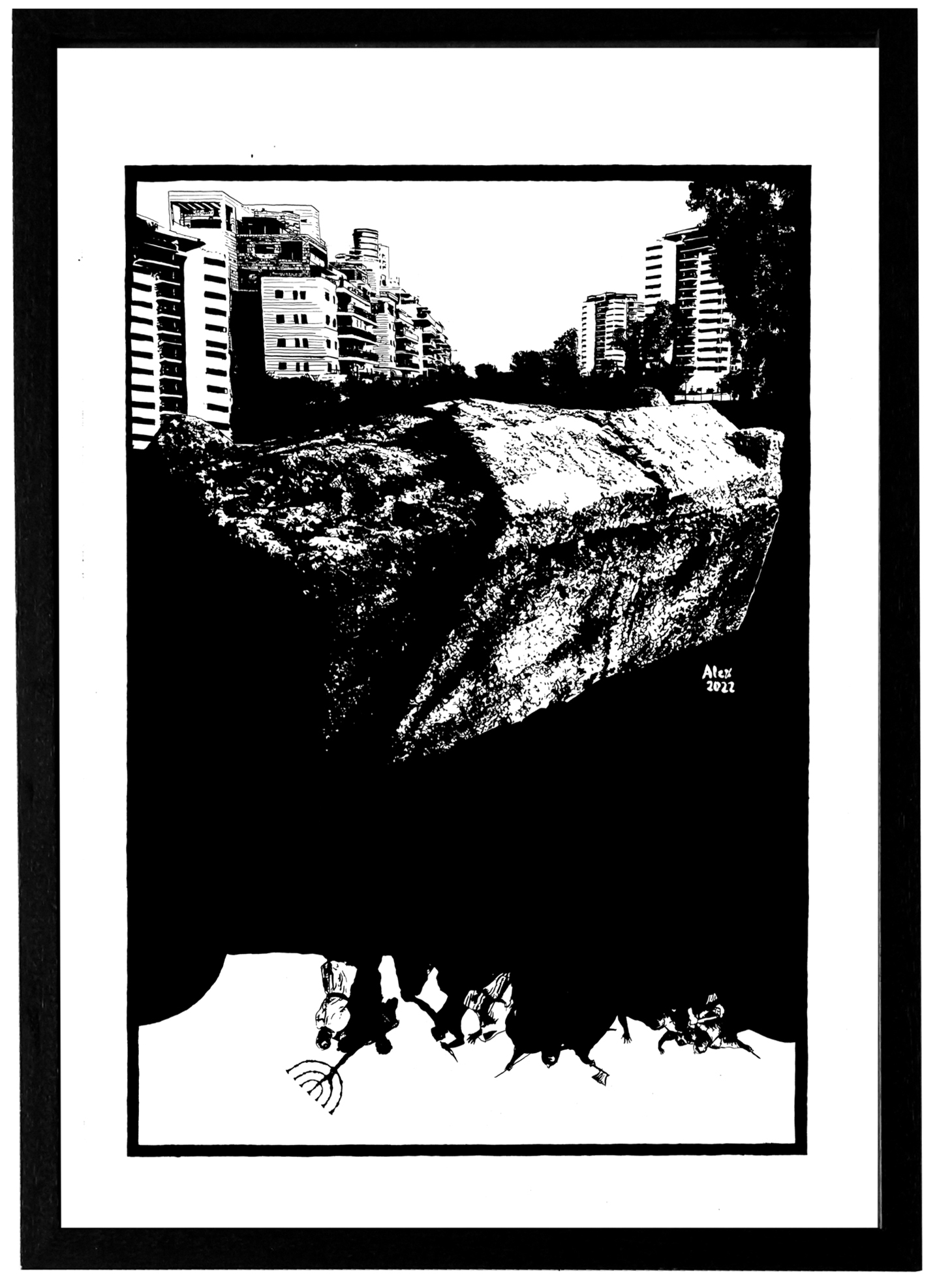

“Rising from the Temple’s ashes (Yavne)”, Alexandre Mitchell, 2022

(Canson, 180g, 42 x 59cm, Indian ink)

The destruction of the second Jewish temple and the city of Jerusalem by the Romans in 70 C.E. was a horrific and momentous event. Just like the plunder and demolition of Solomon’s temple (built around 950 B.C.E) by the Babylonians in 586, it forced the Jews to re-invent themselves as a nation without a temple, or a capital.

Once again, a foreign empire had tried to annihilate the Jewish people by destroying their only temple. It was an attempt to severe their attachment (re-ligio) to their god and destroy their identity as a people. The irreversible devastation of Jerusalem in 70 C.E. acted as a crucible. A Pharisian rabbi, Yohanan Ben Zakkaï, abandoned the city in ruins to establish a school of thought elsewhere. Hidden in a coffin, probably carrying his precious scrolls and the knowledge of his forefathers he was secreted away by his disciples right through the gates of Jerusalem in a coffin and made his way to a coastal town called Jabneh (modern Yavne).

This was the beginning of so-called Rabbinic Judaism. Everything had to be re-thought to ensure the shared past would not be forgotten and new laws established in keeping with a new reality. The exiled sanhedrin of Yavne would eventually replace temple rituals and daily sacrifices by prayers in small houses of prayer and study (synagogues) which changed the face of Judaism and ensured its survival.

In 2021, archaeological excavations in Yavne brought to light a series of stone coffins that may have belonged to sanhedrin members in exile. These finds inspired the sarcophagus in the drawing between the urban landscape of modern Yavne and the destruction of the temple in Jerusalem.

Most artists who have represented the destruction of the temple reveal more of their own culture than that of Jerusalem. The relief on Titus’ arch (81 C.E. dedicated by emperor Domitian) is a well-known image. Its location at the entrance of the Roman Forum was deliberate, to force passers-by to relive the capture of Judea, the sacking of the temple and the distinctive menorah. The Roman coinage of IVDAEA CAPTA found all over the empire served a similar purpose.

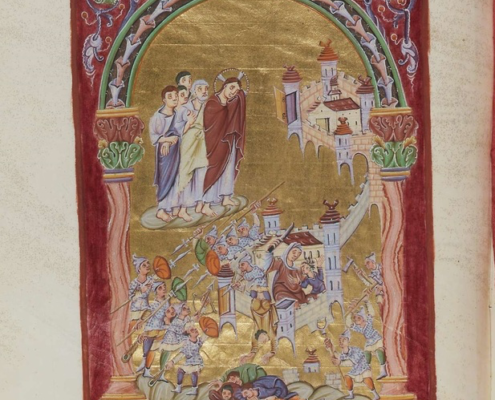

Yet, what may come more as a surprise is that throughout the middle-ages, the scene almost always promoted anti-Jewish sentiment. Take for instance the scenes of the siege of Jerusalem and its destruction in Othon III’s Gospel Book or a 14th century Book of Hours. They showcase a certain Mary of Bethezuba (twice in the same image in the book of hours) who according to Flavius Josephus slaughtered and ate her own child.

In the hands of Christian theologians and commissioned artists, she became the sinful negative type of the Jewish mother to be contrasted to the hopeful Virgin Mary. Cannibalism is known to have happened in numerous sieges and famines throughout history. And the Great Famine of 1315-1317 was marked with extreme scenes of cannibalism and infanticide throughout Europe. But none of these events were instrumentalised like Mary of Bethezuba to shame an entire nation or justify their persecution.

One of the only paintings – regardless of its archaeological inaccuracies – that has no other agenda than to recreate a period piece is Francesco Hayez, Destruction of the Temple of Jerusalem. Now here was a painter with an incredible flair for the dramatic and staged compositions. His preparatory sketches (kept in Venice) inspired part of this painting.

Further reading

- Excavations of Yavne | JPost 29/11/2021

- Arch of Titus | online

- Judea Capta Coinage | Biblical archaeology review | Wikipedia

- City of Yavne | Modern | Ancient Jabneh

- City of Jerusalem | Jewish Encyclopedia

- Yohanan ben Zakkai | Jewish Encyclopedia

- Destruction of Jerusalem Iconography | Exhibition in Nottingham | Galleria Accademia, Venice